I stumbled upon a blog post a few weeks back titled “Why build this blog - or anything - on IPFS?". It intrigued me. IPFS sounded familiar - I remember thinking it was a cool experimental project in the crypto realm. But for the blog I was reading to currently be on IPFS? - it made me think twice about the seriousness of it.

In the post, Beau Cronin talks about some fundamental concerns with our current internet protocols, and how a distributed internet like IPFS can solve many of them. It occurred to me that I’ve never thought about a legitimate alternative to the way the internet works. It just is the internet, right?

Today’s Internet

Our core internet technologies today - DNS, TCP/IP, HTTP, etc - are built to route web addresses to a specific location. Typing in google.com performs a DNS lookup to find out which server to route to. DNS lookup returns IP address 64.233.176.100, so our browser makes a request to that location. Whatever content the server at that location returns is what is displayed.

The internet was built this way - with location based addressing - allowing computers to connect to each other directly. But this approach has drawbacks:

- The user is trusting that they are routed to the correct location, and they’re also trusting that the content hosted on that server is what the user expects - content can be changed at any time without warning.

- Internet traffic is optimized to route through internet ‘backbones’ which causes heavy reliance on centralized connection nodes - like the fiber lines running into AWS data centers. If I request a piece of data from a friend next to me, the traffic will likely route through some centralized server. Centralized servers lead to behemoths that effectively control our internet. (Remember when AWS US-East went down for a day and took half the internet down with it?)

- Bottlenecks and scaling issues arise when there’s only a single data source.

A Distributed Web

IPFS is a protocol for a distributed web that addresses many of these problems.

At its core, it uses content based addressing to link directly to the file contents the user requests. When you make a request, IPFS will crawl the distributed nodes and find the content as efficiently as possible. If your friend sitting next to you has the file cached locally, IPFS can find and return it without any central server in between. This is a much more efficient system for moving data - for video we could see up 60% bandwidth savings - and this is why Netflix is actively experimenting with IPFS today.

This made a LOT of sense to me. For YouTube’s servers to be solely responsible for delivering ALL the video content? That’s an insane amount of bandwidth going through those centralized pipes. A P2P approach distributes the load evenly across the network, making things much more efficient and redundant. Content-based addressing is simply a more user-centric approach. When I want to view a blog post or a video, I don’t care which server I get routed to. I care about the content itself. And distributing the content across millions of peers? It makes our internet virtually indestructible.

I love the idea of a web which is more efficient, reduces our reliance on internet titans, and can verify content at a cryptographic level resulting in a fundamentally safer and more robust web.

So I decided I’d dig in and try it out.

Learning IPFS

I started on ipfs.io to learn the basic concepts. I read through some introduction material and took a lot of notes - trying to summarize what I read to make sure I understood everything.

I found a Gitbook called “The Decentralized Web Primer” which contained a series of tutorials intended to explain core concepts. I know I learn best by building and experimenting - so this series was GREAT. This was my main reference material for the rest - so if you’re interested in following along, check that Gitbook out!

I first installed go-ipfs on my Mac. This includes a CLI. I ran ipfs init and then ipfs cat /ipfs/QmYwAPJzv5CZsnA625s3Xf2nemtYgPpHdWEz79ojWnPbdG/readme - which showed the contents of a file. I wasn’t sure where this came from. I looked in ~/.ipfs directory to see if I could find the file. I couldn’t. It contained lots of cryptic directories under “nodes”. (Turns out the readme file is added locally when you run ipfs init)

I created a simple .txt file in VSCode - containing only my text and added it to ipfs via ipfs add mytextfile.txt. IPFS hashed the raw file content and output:

➜ testdir ipfs add mytextfile.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza mytextfile.txt

7 B / 7 B [==================================================================================================] 100.00%

The file was hashed and IPFS returned the CID (Content Identifier).

I created a second file with the exact same my text content:

➜ testdir ipfs add samecontent.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza samecontent.txt

7 B / 7 B [==================================================================================================] 100.00%

The hash was the same. Interesting! This proved the CID is a hash of the content, not the file.

I ran ipfs add -w mytextfile.txt which added the file and its directory to IPFS.

➜ testdir ipfs add -w mytextfile.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza mytextfile.txt

added QmYi7UyQKuNMhjC43caRCfdAbcFLbvi3de69ArDuqFtd5q

7 B / 7 B [==================================================================================================] 100.00%

The file and directory had separate IDs. We can run ipfs ls to list the directory contents.

I ran cd .. and ipfs add -r testdir which added the full directory (recursively) and listed ALL of the content:

➜ Documents ipfs add -r testdir

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza testdir/mytextfile.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza testdir/samecontent.txt

added QmPCwGkDRjW8B2SHoS3P9Cc4hKDjtdgytrfHQhg8n1BdGE testdir

14 B / 6.02 KiB [>------------------------------------------------------------------------------------] 0.23% 00m13s

What happens if I add a new file? Will the ID of testdir change?

➜ Documents ipfs add -r testdir

added QmUmcERRuYw73a8oHAU58ND8zm2tpQz5aV5EU9Bq55AUu2 testdir/differentcontent.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza testdir/mytextfile.txt

added QmdRCwP8LzudQAgkCVF61D7hP4Y45a42k3R5xvBUQDhxza testdir/samecontent.txt

added QmSdTERdeCmnGhYBY6euEwk8vrpdwfRdDBRndSdC3Hi1g8 testdir

31 B / 6.03 KiB [>------------------------------------------------------------------------------------] 0.50% 00m10s

It did! A directory is a hash of all its contents inside - so if one of its files changes, the directory hash changes too. (Merkle Trees!)

Okay - so far I installed IPFS, created some text files to learn how content is hashed. I created directories to see how directories are hashed with file metadata. I also experimented with pinning, and learned that you should pin content to ensure it is kept around and not garbage collected like the rest of the cache.

Time to go online!

Connecting

ipfs daemon is the magic command. It allowed me to connect to other nodes in the network. I ran ipfs id to learn my node’s identifying information:

➜ testdir ipfs id

{

"ID": "QmNdGU96KW92zVF9oqHCZboBhVKPYjbwHpjgciQPAF54mu",

"PublicKey": "CAASpgIwggEiMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4IBDwAwggEKAoIBAQDa1+jS9VGeq4TnUCLXhakRClZA4YtKhZCzGDMRSKMuKTlVKazlHAzg5CBOxEv/ywIGV1lpIcUsBbAY/s5aTYkANzR+LAhaOS4w9nfL9J670ikFkf4mKeGrrY5VIH5sw7FZx/syszWGoQpaQUypZJNnr9f6HdL1SIEhxIRYsZA9Mvsis6v6H7yxE4LZsrz09m4kgKqpo5W5/cD+VFbpjNROUfy7a4TDmjojk6lmqvU0N79KMWQe/grTyI8Zwnw0pzdqQ9GLsqCoxPXWSLHu+vDyaX/uoBvVs/Ug/lbugUQ0wdTp4M0RGLzIFWsGy//4Gg4OvayaIJuQWXztZ0kEfH5FAgMBAAE=",

"Addresses": [

"/ip4/127.0.0.1/tcp/4001/ipfs/QmNdGU96KW92zVF9oqHCZboBhVKPYjbwHpjgciQPAF54mu",

"/ip4/192.168.1.11/tcp/4001/ipfs/QmNdGU96KW92zVF9oqHCZboBhVKPYjbwHpjgciQPAF54mu",

"/ip6/::1/tcp/4001/ipfs/QmNdGU96KW92zVF9oqHCZboBhVKPYjbwHpjgciQPAF54mu",

"/ip4/107.12.72.210/tcp/28041/ipfs/QmNdGU96KW92zVF9oqHCZboBhVKPYjbwHpjgciQPAF54mu"

],

"AgentVersion": "go-ipfs/0.4.23/",

"ProtocolVersion": "ipfs/0.1.0"

}

Then ran ipfs swarm peers to look at other peers in the network:

➜ testdir ipfs swarm peers

/ip4/104.131.131.82/tcp/4001/ipfs/QmaCpDMGvV2BGHeYERUEnRQAwe3N8SzbUtfsmvsqQLuvuJ

/ip4/104.236.179.241/tcp/4001/ipfs/QmSoLPppuBtQSGwKDZT2M73ULpjvfd3aZ6ha4oFGL1KrGM

...100s of them!

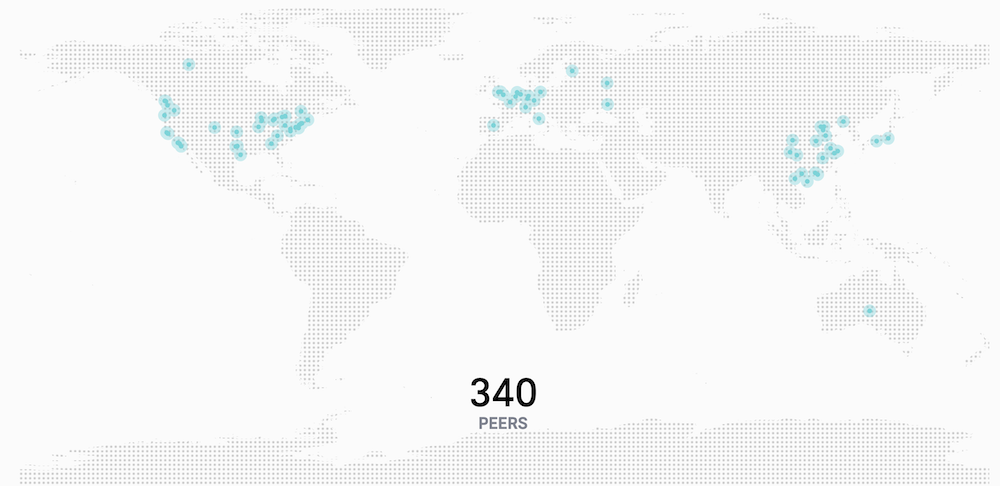

The webUI that gets spun up is pretty sweet too - http://127.0.0.1:5001/webui. I spent some time poking around, looking at peers, exploring files on the network. It was cool to see IPFS in action!

Running the daemon allowed me to view content hosted on other nodes. I found XKCD on IPFS in the ‘Explore’ section and printed out 100 - Family Circus - transcript.txt by its CID:

➜ testdir ipfs cat QmWWK62bgMxWd8TrrouN8Hrv4Tq9dzofsiQoZkZudJ5TEd

[[Picture shows a pathway winding through trees to a sink inside a house, out to some swings and back to ths sink, out to a ball and back to the sink...]]

Caption: Jeffy's ongoing struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder

{{alt text: This was my friend David's idea}}%

So cool! IPFS was able to find the peer with the content and return it over the network.

At this point, IPFS was making sense to me. Running the daemon made me a node in the network, and anyone else on IPFS could retrieve data from me, or use me as step to connect to any of my connected peers.

But I still had a lot of questions, like - how can my website be hosted on IPFS and accessible through a normal browser?

To view IPFS content the browser either needs to become a node - achieved through browser extensions - or proxy requests through a server that acts as a node - an IPFS gateway. I can’t rely on every website visitor to install a browser extension, so I needed to use a gateway.

I was thinking - doesn’t this defeat the purpose of IPFS, if I need to rely on a server to process my request?

Yes. Absolutely.

But the reality is that in order for IPFS to gain adoption, it needs to work seamlessly with the tools we have today - normal browsers, no binaries or browser extensions required. In a perfect world, a transition to IPFS should hardly be noticeable by the user - and IPFS gateways are the best solution today to bridge the gap.

Hosting the Website

You’re reading this on my blog in the future state - but I started with a REALLY simple index.html and image. As much as I wanted to spend time designing and crafting a beautiful website, I was dealing with a brand new technology here, and the smart (less fun) option is always to start with the simplest example possible. Get it running, and then expand on it.

I created my basic HTML and image and added the directory to IPFS.

<!-- index.html -->

<html>

<body>

Justin Poliachik <img src="profile.jpg" />

</body>

</html>

➜ Documents ipfs add -r justinpoliachik

added QmZo9HC9E5e2C1cXxagH4SeE2fQvDA1SJgqgn3TX3ud4pB justinpoliachik/index.html

added QmUjMa74rVNwYyd3h4Uo6KZ5pVfktKecQ1nw3SrDBiA6yC justinpoliachik/profile.jpg

added Qma9ouEoyXkixvpJKxWaVckCboJBXMzs3o5hjp12yTfRaW justinpoliachik

20.29 KiB / 20.29 KiB [======================================================================================] 100.00%

Using the directory ID I was able to view the content locally in a browser at http://127.0.0.1:8080/ipfs/Qma9ouEoyXkixvpJKxWaVckCboJBXMzs3o5hjp12yTfRaW/

But every time I updated it, the link would change (as expected). I experimented with IPNS (InterPlanetary Naming System) to create a static address with a mutable ‘pointer’ to content, but quickly learned that performance issues are a real thing. IPNS entries are stored in a distributed hash table across nodes in the network, so it makes sense that accessing content would be slightly slower than raw IPFS, but it was noticeably slow and borderline unusable. I opted to continue using IPFS knowing that I’d need to update address references on every website publish, and wait to see if IPNS improves in the future.

Now my website was accessible via IPFS, but how would I guarantee the content would stay available? I was running the IPFS daemon on my Macbook, but my content wouldn’t be accessible without it active. Beau’s blog post pointed me to Pinata.cloud - a clean and simple service to pin IPFS content and guarantee availability. I signed up, got my API keys, and was able to pin my website almost instantly with a single API call (I used Postman). I stopped my local daemon and tried to load my site - http://ipfs.io/ipfs/Qma9ouEoyXkixvpJKxWaVckCboJBXMzs3o5hjp12yTfRaW/ - it still worked! Proving that Pinata pinned my content and was working as expected.

My “website” was published and ready, the last step was figuring out the best way to redirect justinpoliachik.com to it. A basic redirect would change the URL to gateway.ipfs.io which I didn’t want. I needed to use an Alias record and DNSLink. As a networking n00b I really didn’t understand the specifics of how this works - but I read a few blog posts, and my basic understanding was to:

Create an ALIAS record for justinpoliachik.com which forwards traffic to 209.94.90.1 (gateway.ipfs.io). Any IPFS gateway would work here.

Create a TXT record using the name _dnslink.justinpoliachik with the TXT content "dnslink=/ipfs/Qma9ouEoyXkixvpJKxWaVckCboJBXMzs3o5hjp12yTfRaW" would map the domain name to the IPFS content ID. This is called DNSLink.

Now, when I load justinpoliachik.com, DNS finds the alias to 209.94.90.1. The browser connects to 209.94.90.1 with a HOST: justinpoliachik.com HTTP header. The IPFS gateway reads the header and - recognizing a dns name - checks for the associated DNSLink at _dnslink.justinpoliachik.com - finds the ipfs path and loads the content. WHEW!

It worked! I was now hosting my website on IPFS! :confetti:

Next steps:

- Create a blog. I’m planning on using Hugo as a static site generator for Markdown posts.

- Host code on GitHub

- Use GitHub actions to publish updates to site, including updating the DNSLink record.